|

In the space of one week last spring, I saw three movies: United 93, recounting one of the most tragic days in American history; Army of Shadows, an unsparing and mournful portrayal of the dangers faced by the French Resistance during World War II; and Art School Confidential, a movie about…art school.

Guess which movie made me want to open a vein.

I said as much leaving the theater where Art School Confidential was playing: "That was a movie to slit your wrists by." Without missing a beat, the friend who saw the film with me replied, "That made Heart of Darkness look like Mickey Mouse."

If Art School Confidential had been ineptly made, it could be dismissed. Technically speaking, it's pretty much unimpeachable. Director Terry Zwigoff and his co-screenwriter, Daniel Clowes, are experts in the depiction and skewering of human foibles, particularly those that fall within the realm of artistic pretense. In making their characters fall on the swords of their own folly, they are as skillful as anybody making film comedies today, deserving rank with such modern masters as Christopher Guest and Larry David. But Guest's characters are gently self-deluded, while the more cynical David is careful to make even such characters as George Costanza endearing on some level. In Art School Confidential, the only likable character is Sophie, the art theory professor played by Anjelica Huston, and she receives so little screen time that it's difficult to discern her character's purpose. Matthew (Nick Swardson), the flaming gay design student who thinks he's in the closet, might have been sympathetic, but Zwigoff and Clowes choose instead to play him for cheap laughs.

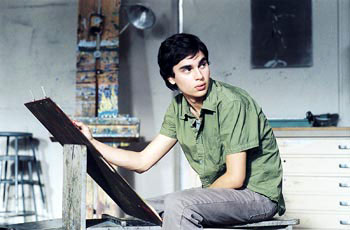

Every other character in the film is a swine. Even Jerome Platz (Max Minghella, son of Anthony), the Candide-like freshman drawing student we're primed to root for at the beginning, turns out to be just as corrupt and self-serving as everyone else.

When Jimmy (Jim Broadbent), the drunken Falstaff-Caliban character who becomes Jerome's artistic mentor, says, "Fuck the whole human race," Jerome takes up that cry as his own, and there is nothing in the rest of the film to suggest that it isn't Zwigoff and Clowes' cry too. When Mark Twain denounced "the damned human race," it was because Twain believed in ideals his fellow human beings seemed determined to desecrate. If Zwigoff and Clowes have ideals, it isn't evident from Art School Confidential. Apparently they think people are bastards, period.

Many reviewers have decried Art School Confidential for lacking the compassion of the previous Zwigoff-Clowes collaboration, Ghost World. While I agree that Ghost World is by far the better of the two, I'm not sure how much compassion that film contains—though the original Ghost World, the graphic novel by Clowes, contains plenty. Enid Coleslaw, the story's protagonist (the name, of course, is an anagram of Daniel Clowes), is a teenager just graduated from high school who drips sarcastic contempt for the world around her. The episodic story has Enid and her best friend Becky—aided reluctantly by their pal Josh, who semi-secretly has a crush on both—tail various odd characters around their town, playing the occasional elaborate practical joke on some of them. The basic point of the story is Enid's gradual realization—as Becky and Josh fall away from her, and her few hopes come to nothing—that having a hip, disenchanted attitude just isn't enough to make her special.

The beauty of Ghost World—besides Clowes' precise, subtly mocking style of drawing—is its elusive, funny-sad tone, the ironic humor giving way gradually to melancholy. Its delineation of adolescent loneliness and despair has been compared, justifiably, with The Catcher in the Rye. Toward the end of the book, Enid tells Becky of her secret plan to "just get on some bus to some random city and just move there and become this totally different person." At the end, when the bus finally comes and a much subdued Enid boards it, the meaning is ambiguous, but it certainly doesn't signify the panacea for Enid's problems.

The Zwigoff-Clowes film of Ghost World succeeds remarkably in capturing the book's ironic, pensive tone. (The casting is right, too; Thora Birch, Scarlett Johansson and Brad Renfro are dead ringers for Clowes' drawings of Enid, Becky and Josh.) The film, however, makes a couple of major changes to the plot that alter its thrust, and not for the good.

First, the film makes Enid an aspiring artist, and puts her in a class with a ditzy instructor named Roberta (played by Illeana Douglas) who values social commentary over talent. (However, this subplot isn't a total dry run for Art School Confidential; Roberta, whatever her faults, is kind and well-meaning.) Second and more ominously, Zwigoff and Clowes take a minor character from the book—a lonesome loser on whom Enid and Becky play their cruelest prank—and expand him into Seymour, a middle-aged blues record collector who briefly becomes Enid's love interest. I say "ominously," because I suspect Seymour is all Zwigoff and no Clowes. Zwigoff's first film was Crumb, a brilliant, profoundly disturbing documentary about the famously maladjusted underground artist. Seymour bears little resemblance to any character in the original book of Ghost World, but he could easily be not only a character from R. Crumb, but Crumb himself. That perception is enhanced by the casting of Steve Buscemi, who looks like he walked out of the pages of Zap Comix, as Seymour. I don't wish to take anything away from Buscemi's masterful tragicomic performance, proving him once again one of our finest character actors. But it becomes apparent that Seymour's main purpose is to be Enid's whipping boy. Instead of Clowes' compassionate laughter, Seymour is surrounded by Crumb's (and Zwigoff's) cold mockery. The first time I saw the movie, I thought it was far too hard on Seymour and far too easy on Enid. Seeing it a second time, I felt Enid's pain more deeply, as well as her genuine feelings for Seymour. But I still felt that her behavior toward Seymour was wantonly cruel. At the end of the movie, when Enid boards the bus, it really is a deus ex machina, while Seymour is left behind, his life in ruins because of her. The moral, though not stated baldly, is clear: hip, detached irony is the only attitude to have in life. To care deeply about anything is to be a dork.

In Art School Confidential, the flip sarcasm becomes blatant. The scenes of freshman art students arriving at the fictional campus of Strathmore College—portrayed as bucolic and peaceful in the brochure, but surrounded by more urban blight than every bar combined that was ever patronized by Charles Bukowski—set the tone. One young woman emerges barefoot from her car, exulting in her new freedom, and promptly steps on a broken beer bottle. None of the other students receives such an immediate shock, but those shocks will be coming shortly.

As long as Zwigoff and Clowes stick to comic grotesques and the senseless, hothouse politics of art school, the movie is fine, even laugh-out-loud funny. (The trailer for the film is one of the best I've seen in years, highlighting the efforts of dim art-world wannabes to gain attention by self-administering electric shocks and having giant canvases fall on them.) Three performances stand out. Ethan Suplee (of Cold Mountain and My Name is Earl) plays Vince, an insufferable film student obsessed with making an interminable, indecipherable epic about a serial strangler who threatens the campus. John Malkovich (who also co-produced both this film and Ghost World) is in his full reptilian glory as "Sandy" Sandiford, an amalgam of every possible negative quality an art school professor can have. ("I want to help you find yourself," Sandy tells Jerome, and from the way he lays his hand on Jerome's knee, we know exactly what he means.) The aforementioned Jim Broadbent is a bitter, sodden wonder as Jimmy, a Strathmore burnout who has encountered his share of Sandy Sandifords and needs a quart of slivovitz a day to dull the memory.

The film goes seriously wrong, however, both in its portrayal of the main character, Jerome, and in the campus strangler subplot, which I understand did not exist in the original Clowes cartoons. Jerome has been pounded by bullies and ignored by girls through all twelve grades of school. (The latter is made unbelievable by the casting of the poutily handsome Minghella.)

He wants only to become a great artist, or at least be regarded as one, all the better to attract girls to his bed. His drawings still have a certain student awkwardness, but they are infinitely more promising than those of his self-satisfied art school classmates. For this, he is reviled and mocked in his art classes more fiercely than he was in high school. Jerome's classmates and teachers are mostly blind to his superior talent, and to the extent they recognize it, they resent it. (What they themselves lack in talent, they compensate for in attitude—they're all pretentious, snobbish sycophants.)

Prizing novelty and shock value above all else, they go into raptures over the rudimentary scrawls of Jonah (Matt Keeslar), a square-jawed, mysterious man's man who quickly becomes Jerome's worst enemy. Adding to Jerome's anger and despair is Audrey (Sophia Myles), a gorgeous artists' model who at first warms up to Jerome but later seems to have eyes only for Jonah. The last straw comes at an important art-show opening, to which Jerome can gain admittance only by serving as bartender. He sees Jonah and Audrey there, as a couple and as invited guests, and something snaps.

It probably isn't fair of me, to those of you who haven't seen the film, to say precisely how Jerome snaps, or what happens as a result. Let's just say that for Jerome to commit an act of fraud, and later to allow himself to be charged with a far more heinous crime for publicity's sake, doesn't exactly endear him to us. And if Jerome isn't endearing, the film is lost. I appreciate that Zwigoff and Clowes wanted to subvert the old template of a young idealist encountering obstacles, losing his way, and finally finding himself again. But the way they do it blows past cynicism into the realms of misanthropy and nihilism. Some reviewers claim the ending is happy, but I fail to see what's so happy about Jerome and Audrey having their first kiss through the glass partition of a prison visiting room. Zwigoff and Clowes leave them, and the audience, dangling.

Having introduced the worst, Zwigoff and Clowes don't even have the courage to take it to its logical conclusion. When Stanley Kubrick dropped the bomb at the end of Dr. Strangelove, it wasn't happy, but it was satisfyingly cathartic. If Zwigoff and Clowes had had the guts to show Jerome chatting with his agent about his artistic legacy as he's strapped to the gurney and the lethal injection prepared, they might have had a satire of Swiftian proportions.

But then again, every character in the movie is too petty to support a major satire. Audrey is all over the map, changing constantly into whatever Zwigoff and Clowes need her to be in any given scene. Jonah is the preliminary sketch of an interesting character. There's a vastly simplified Enid surrogate in the person of Bardo (Joel David Moore, no relation to this reviewer), a professional student who majors in drinking, screwing, and pigeonholing his classmates in belittling ways. "Now I know who you are," he tells Jerome after the latter has poured out his heart to him. "You're the class douchebag." "Douchebag" is the word I would use to describe Bardo; Zwigoff and Clowes, however, present him as the disabused, clear-eyed speaker of truth.

Art School Confidential bears only the most superficial family resemblance to Ghost World, at least as Clowes originally wrote it. It does, however, bear more similarities to the film version of Ghost World than most critics have acknowledged. The subtle, melancholy art of Daniel Clowes gives way to the brazen misanthropy of R. Crumb and his acolyte, Terry Zwigoff. I don't know what others may think, but for me, Zwigoff has been a bad influence on Clowes artistically—though I'm sure their partnership has been great for Clowes' bank account. To paraphrase George S. Kaufman, subtlety is what closes on Saturday night.

|