|

Part One

Not tut ein Held, Wagner wrote in Die Walk√ľre (Act II;scene 1) – "We need a hero who is free of divine protection, free from the rule of the gods," he continued. He was, of course, referring to his superhero of the Ring cycle, Siegfried, but the phrase prophetically came to describe Wagner's and opera's search throughout the years for the singers to incarnate the Meister's larger-than-life characters. On this 200th anniversary of Richard Wagner's birth, as it has for the more than one hundred seventy years, the tenors who perform Wagner's difficult and demanding music belong to a very elite confraternity, and the development of their Fach, or vocal type, has been the subject of controversy, lament or praise, for as long a singers have undertaken these roles.

At the time I published my book-length study in 1989 (We Need a Hero: Heldentenors from Wagner's Time to the Present, Weiala Press), there was much disagreement about the true nature of the Heldentenor voice, and critics were voicing frequent complaints that the golden age of Wagner singing was gone, and that there were no true heroic voices left. My study sought to demonstrate that the Heldentenor had evolved through a process of change, growth, and refinement into a new breed of artist equal to the expectations of 20th century opera aesthetics. The late 20th century Heldentenor, I had argued, by "a powerful process of ascending evolution had emerged a vitally redefined artistic presence – one which fulfills with radiant perfection the dream of Wagner's art: to combine vocal power and opulence with dramatic and psychological truth" – to achieve Wagner's ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk.

In the twenty-five years since publishing that study, the Heldentenor voice continues to evolve, though it seems to me that the greatest developments had already taken place by the end of the 20th century, and thus it seems fitting to recall some of the great singers of the past who have laid the groundwork for the kind of artist we admire today as a Wagnerian tenor. To do that we need an abbreviated overview of the changing aesthetic and styles of Heldentenor singing from 1842 when Wagner mounted his first grand opera, to present-day performances at Bayreuth, the Wagnerian festival the composer established in 1876.

The term "Heldentenor" simply means an heroic tenor. The voice is customarily thought of as being large, having a strong baritonal foundation with a range of two octaves. The designation can apply to repertoire other than Wagner's operas, but it is the Meister's work which has defined the Fach. And therein lies the first difficulty in defining the voice because Wagner's opus from Rienzi to Parsifal calls for differing vocal qualities, sometimes within the same work.

For the longest time the German tradition liked to speak of several different sub-categories of Heldentenor voices. The jugendlicher Held (young hero) typically sings the youthful heores like Walther von Stolzing in Die Meistersinger or Erik in Der Fliegende Holländer. His is a voice which is ringing, brilliant, radiant, growing from the Italianate tradition and making use of a more cantabile rather than declamatory style. The Heldentenor proper relies on his dominant chest register and allows a metallic, dark timbre and declamatory style to prevail to a greater degree. He sings Siegmund, Tristan, and Parsifal.

Then, just as repertoire can be divided into types, so the vocal color and production of the voice are often separated into schwer and echt Tenors. The schwer Tenor refers to a voice in which the upper register is founded on a strong, dark, baritonal base, while the echt Tenor is a lighter sounding, more forwardly placed voice. And then, too, there are the distinctions in the style of singing: bel canto from the Italian tradition relying on long line, full vowels, and legato, and Sprechgesang, the declamatory speech-song style which eschews excessive Italian portamenti (sliding form one note to the next) in favor of cleaner attacks and incisive articulation of text.

That these designations are mostly critical conventions immediately becomes apparent when one realizes that undertaking almost any one of Wagner's heroic roles requires a blend of all these techniques, and while a singer may possess one quality more than another, he ultimately will need a foundation in all of them to succeed in Wagner. The development of the Heldentenor voice over the centuries has witnessed a growing synthesis of jugendlicher and heroic, schwer and echt, bel canto and declamatory methods, at the same time that theatrical, dramatic values have evolved. In the last decades of the 20th century, this synthesis was most daringly and satisfying realized in the work of singers like Jess Thomas and Peter Hofmann and in the staging of directors like Patrice Chéreau. Their legacies, and those of the seventeen other great Heldentenors remembered in this article, continue and today in singers like Jonas Kaufmann, Johan Botha, Lance Ryan, and Klaus Florian Vogt.

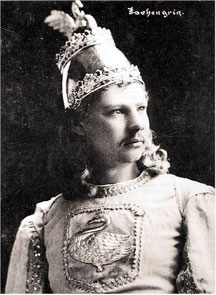

Three Heldentenors who were associated with Wagner's operas in the composer's lifetime serve as the foundation for the art of heroic tenor singing.  Josef Aloys Tichatschek (1807-1886), the tenor who had the longest relationship with the composer, can appropriately be called the first Heldentenor. He reigned in Dresden for thirty years, where he created the title roles of Wagner's Rienzi, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin. Tichatschek, who had studied with Rossini's pupil Giuseppe Ciccimarro, was trained in the Italian style. The contemporary music critic Henry Chorley described Tichatschek's voice as "strong, sweet, expansive, taking the altissimo notes of his register in chest tones." (in Modern German Music 1839). Most likely Tichatschek was an echt Tenor,at home in the high tessitura of Rienzi;his bel canto foundation combined with limitless volume gave his voice a beauty of sound as well as heroic outpouring. Josef Aloys Tichatschek (1807-1886), the tenor who had the longest relationship with the composer, can appropriately be called the first Heldentenor. He reigned in Dresden for thirty years, where he created the title roles of Wagner's Rienzi, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin. Tichatschek, who had studied with Rossini's pupil Giuseppe Ciccimarro, was trained in the Italian style. The contemporary music critic Henry Chorley described Tichatschek's voice as "strong, sweet, expansive, taking the altissimo notes of his register in chest tones." (in Modern German Music 1839). Most likely Tichatschek was an echt Tenor,at home in the high tessitura of Rienzi;his bel canto foundation combined with limitless volume gave his voice a beauty of sound as well as heroic outpouring.

For all his vocal gifts, however, Tichatschek was said to lack dynamic subtlety, forte being his preferred mode, and his histrionic ability was reported to be risible. He was a stock actor who never understood Wagner's desire for dramatic and psychological reality. Nonetheless, Tichatschek must be credited with shaping the sound of the Heldentenor voice: a clarion instrument supported by bel canto values. Though he never did master the declamatory aspects that later artists did, he made a huge contribution to Wagner's art by popularizing the composer's early operas and by embracing "the music of the future."

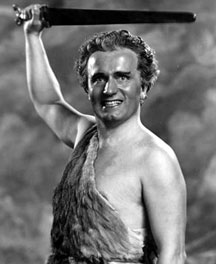

If Wagner was fond of Tichatschek, he found his collaboration with Albert  Niemann (1834-1861) to be a stormy battle of wills. Niemann premiered Tannh√§user in Paris for the composer in 1861 and went on to sing Sigmund in the first Ring cycle at Bayreuth in 1876; he also sang in Der fliegende H√∂llander and Die Meistersinger. He was praised for his handsome, riveting stage presence. His voice, which was likely a schwer Tenor, stirred some controversy. Hans von B√ľlow found him to be "a toneless, pushed up baritone" though Alexandre Flamant described him as having a "clear, virile tenor voice"(in Der Reiche der T√∂ne 1890). Niemann mastered the art of Sprechgesang (speech-song) which Wagner used increasingly in his work. His voice was not conventionally beautiful, but he used it to deliver the text with searing intensity. He was, by all accounts an indifferent musician, and though a compelling actor, certainly not an ensemble player. Niemann (1834-1861) to be a stormy battle of wills. Niemann premiered Tannh√§user in Paris for the composer in 1861 and went on to sing Sigmund in the first Ring cycle at Bayreuth in 1876; he also sang in Der fliegende H√∂llander and Die Meistersinger. He was praised for his handsome, riveting stage presence. His voice, which was likely a schwer Tenor, stirred some controversy. Hans von B√ľlow found him to be "a toneless, pushed up baritone" though Alexandre Flamant described him as having a "clear, virile tenor voice"(in Der Reiche der T√∂ne 1890). Niemann mastered the art of Sprechgesang (speech-song) which Wagner used increasingly in his work. His voice was not conventionally beautiful, but he used it to deliver the text with searing intensity. He was, by all accounts an indifferent musician, and though a compelling actor, certainly not an ensemble player.

Niemann put his own stamp of originality on the roles he played, and his work as a singer cannot be assessed separately from his performance as an actor. Albert Niemann made unique contributions to the Heldentenor art, most of which were not musical, and he remains, among the early Heldentenors a quirky, idiosyncratic, but highly convincing artist. He took Wagner's music beyond the sheer musicality of Tichatschek and pointed artists and audiences toward operatic performances which stressed visual clarity, powerful acting, and integrated text and music.

The third heroic tenor of Wagner's day was also his beloved favorite,  Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1836-1865). His career was the shortest of the three Рonly ten brief years before he died of heart failure exacerbated by typhoid in 1865 shortly after his first Tristans; yet he made the greatest impact in shaping the future of Heldentenor singing. His repertoire included German roles in Der fleigende Höllander, Fidelio, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin as well as Italian standards like Lucia, and Lucrezia Borgia. He created the demanding role of Tristan singing opposite his wife Malvina in Munich in 1865. Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1836-1865). His career was the shortest of the three Рonly ten brief years before he died of heart failure exacerbated by typhoid in 1865 shortly after his first Tristans; yet he made the greatest impact in shaping the future of Heldentenor singing. His repertoire included German roles in Der fleigende Höllander, Fidelio, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin as well as Italian standards like Lucia, and Lucrezia Borgia. He created the demanding role of Tristan singing opposite his wife Malvina in Munich in 1865.

His voice was described by his famous soprano Schroeder-Devrient as one which "soars up to the high notes and rings out very beautifully. It is rich and powerful…He has natural talent, fire, and an inherited sense of rhythm." Moreover, despite his overweight physique, he was said to cut an appealingly heroic figure on stage; he moved with grace, dignity, and expressiveness, and he was known to be an intelligent singing-actor. His temperament was gentle, poetic, soulful, and he eschewed the virtuosity on which Niemann thrived. He believed that an artist's mission was to create in service to the composer – a rather modern concept for its day, one which endeared him to Wagner. He sang his roles, including the fearsomely demanding Tristan uncut, and he focused on fusing music, text, and acting in his performances. As the impresario Leo Damrosch wrote, Schnorr was " the poet whom every singer, actor, musician can be…a man full of spirituality and strength of character."

Schnorr von Carolsfeld's singing brought characters to life from within; he inaugurated a revolutionary new approach for singing-actors, especially Heldentenors. His voice fused echt and schwer Tenor styles, and he demonstrated that a sustained vocal line and rounded tone of the bel canto could be synonymous with the new declamatory style. Above all, his career was testimony to the fact that singing was inseparable from acting, for both took their inspiration from the soul of the dramatic work. Though he died shortly after his historic Tristan, the bereft Wagner recognized the impact he had made: "with the recognition of Schnorr's immense importance for my own artistic creation, a new spring of hope has [sic] arrived in my life." Schnorr demonstrated that the Gesamkunstwerk could be a reality.

In the years from 1883-1910 with Wagner, Schnorr, Tichatschek all dead, Niemann retired, and Bayreuth in Cosima Wagner's questionable artistic hands, the future of the Heldentenor seemed uncertain.  Happily the famous Polish tenor Jean de Reszke's (1850-1925) made the decision to embrace the Meister's repertory and thereby gave continuity to the tradition. Trained with the renowned Manuel Garcia and Pauline Viardot, de Reszke's vocal technique was also based on the bel canto tradition. He began his career in Italian roles, singing as a baritone, but after a hiatus for further study, he reemerged in 1884 as a tenor. He sang a wide repertoire from the lyric Don Ottavio to the dramatic Radamès before becoming smitten by the part of Stolzing in Die Meistersinger which he saw at Bayreuth in 1888. Making his Met debut in 1891 as Romeo and singing German roles in Italian, in 1985 he finally undertook his first Tristan in German. For the remainder of his career he created memorable characterizations of both Siegfrieds, Lohengrin, and Stolzing in the original language at the Met, contributing to New York's wave of Wagner frenzy. His stage career came to a sad end at fifty-five due to a series of indispositions. He returned to Paris to teach, but suffered more tragedies during World War I, including the loss of his son and the invalidism of his wife. Happily the famous Polish tenor Jean de Reszke's (1850-1925) made the decision to embrace the Meister's repertory and thereby gave continuity to the tradition. Trained with the renowned Manuel Garcia and Pauline Viardot, de Reszke's vocal technique was also based on the bel canto tradition. He began his career in Italian roles, singing as a baritone, but after a hiatus for further study, he reemerged in 1884 as a tenor. He sang a wide repertoire from the lyric Don Ottavio to the dramatic Radamès before becoming smitten by the part of Stolzing in Die Meistersinger which he saw at Bayreuth in 1888. Making his Met debut in 1891 as Romeo and singing German roles in Italian, in 1985 he finally undertook his first Tristan in German. For the remainder of his career he created memorable characterizations of both Siegfrieds, Lohengrin, and Stolzing in the original language at the Met, contributing to New York's wave of Wagner frenzy. His stage career came to a sad end at fifty-five due to a series of indispositions. He returned to Paris to teach, but suffered more tragedies during World War I, including the loss of his son and the invalidism of his wife.

The Mapelson cylinders of his voice seems to suggest that De Reszke was an echt Tenor with a forwardly placed sound. Over the years he worked to extend his range upward (he was said to sing dazzling high C's), and he preserved the cantilena of the French-Italian line even in his German roles. He cut a handsome, charismatic figure on stage; he projected a virile realism and romantic aura, and he refrained from divo posturing. Like modern opera singers, he was one of those singers whose artistry was inseparable from the theatre itself.

Not only did de Reszke popularize Wagner's operas abroad, but he also internationalized the Heldentenor repertory, opening it up to non-German singers. With his excellent linguistic skills, he taught singers to respect the original language of the text as an integral part of the musical line. He continued the fusion of echt and schwer Tenors that Schnorr had begun and the blending of bel canto and declamatory styles. Most of all, de Reszke left his mark as a teacher. In the revolutionary thrust of his own career, in the novel standards he established in his own Heldentenor characterizations, as well as in his transmission of those techniques to others, Jean de Reszke imparted a great legacy.

De Reszke's most notable successor was Bohemian born tenor Leo Slezak, (1873-1946) who rose to prominence at the Met, in Vienna (under Gustav Mahler) and throughout Europe in a thirty-eight year career spanning the turn of 19th-20th centuries.  He sang a wide range of heroic roles: Lohengrin, Stolzing, Tannhäuser, Otello, Canio, and Manrico. Mahler called Slezak's voice an Eigenstimme, a singular instrument with its own easily recognizable qualities. Recordings confirm that he was an echt Tenor, comfortable in the high register with a bright, trumpeting, non-baritonal sound that likely was reminiscent of Tichatschek's. The voice was large, liquid, and genuinely heroic housed in a strapping six-foot-four frame. He made effective, emotional use of vibrato, and though his style was not essentially declamatory, he used inflection to deliver textual clarity. Critics suggest that he grew as an actor throughout the course of his career, and if he did not equal Schnorr or de Reszke in this department, he nonetheless projected sincerity and humanity. He sang a wide range of heroic roles: Lohengrin, Stolzing, Tannhäuser, Otello, Canio, and Manrico. Mahler called Slezak's voice an Eigenstimme, a singular instrument with its own easily recognizable qualities. Recordings confirm that he was an echt Tenor, comfortable in the high register with a bright, trumpeting, non-baritonal sound that likely was reminiscent of Tichatschek's. The voice was large, liquid, and genuinely heroic housed in a strapping six-foot-four frame. He made effective, emotional use of vibrato, and though his style was not essentially declamatory, he used inflection to deliver textual clarity. Critics suggest that he grew as an actor throughout the course of his career, and if he did not equal Schnorr or de Reszke in this department, he nonetheless projected sincerity and humanity.

Slezak's principal legacy is musical rather than dramatic. More clearly than any of his predecessors, Slezak demonstrated that heroic singing was compatible with beauty of tone, precision of inflection, and the softer dynamics. An accomplished Lieder singer, he brought the lessons of the recital stage to the opera house. He grafted onto the purity of his musical line a textual scrupulousness and an emotional intimacy. The Bohemian tenor contributed to the Heldentenor art this new concept whose effects would be felt up until the present: he fused chamber dynamics with heroic sound. And beyond this extraordinary technique and interpretive skill, Slezak brought to the Heldentenor repertoire – indeed, to all his roles – that "indefinable something that spells the difference between an excellent singer and a great one" which his son Walter sums up as musicianship, interpretation, and "his great, good heart."

The Heldentenor who inherited the torch from Leo Slezak is often hailed as the greatest incarnation of the breed.  For many the Danish-born Lauritz Melchior ((1890-1973) is the epitome of the Wagnerian singer. He began his career as a baritone, but retrained with Wilhelm Herold and debuted as Tannhäuser in 1918 in Copenhagen. From there he went on to perform the schwer Tenor repertoire in European capitals and at Bayreuth until 1931, when his ardent anti-Nazi feelings prompted him to quit Germany. And as tensions rose in Europe, committed himself to a career in New York. His twenty-four year tenure at the Metropolitan Opera made him the longest reigning Heldentenor in the company's history, and his performances with Kirsten Flagstad became the stuff of legend. For many the Danish-born Lauritz Melchior ((1890-1973) is the epitome of the Wagnerian singer. He began his career as a baritone, but retrained with Wilhelm Herold and debuted as Tannhäuser in 1918 in Copenhagen. From there he went on to perform the schwer Tenor repertoire in European capitals and at Bayreuth until 1931, when his ardent anti-Nazi feelings prompted him to quit Germany. And as tensions rose in Europe, committed himself to a career in New York. His twenty-four year tenure at the Metropolitan Opera made him the longest reigning Heldentenor in the company's history, and his performances with Kirsten Flagstad became the stuff of legend.

Melchior may well have possessed the largest voice of any of the great Heldentenors; its dark, full sound could cut through any orchestra, and he could produce secure single top notes, though he was never completely comfortable in sustained high tessitura. He had a firm grasp of legato and melodic line, though he eliminated portamenti in favor of a cleaner note-to-note flow that set the stage for later 20 century Heldentenors. Never a particularly musicianly singer, he often had troubles with tempi, so much so that once an exasperated Bruno Walter told him, "Melchior, my left hand is exclusively yours!" (New York Times 1973).

His repertoire was limited, and over his long career, his interpretation of roles rarely evolved despite the fact that he set records for number of performances – 223 Tristans or 183 Lohengrins, for example! Melchior considered himself a singer first (and a bit of a divo), and did not trouble himself much over dramatic verisimilitude. There is the famous story of how he would sidle to the wings and disappear for a beer backstage during the Act I Grail scene in Parsifal, when his character was supposed to stand for forty-five minutes in silent awe.

Listen to Lauritz Melchior: Winterst√ľrme wichen im Wonnemond/Siegmund/Die Walk√ľre

Lauritz Melchior brought to the Heldentenor tradition vocal grandeur: volume, tonal beauty, legato, effortless voice production, stamina, and reliability. The aural beauty and sensuous sound he offered went a long way in converting listeners to the thrill of Wagnerian opera. For many, critic Harold Schonberg's assessment would describe Melchior: "In many ways the Heldentenor species died with him. He had the most heroic voice of any singer today, and it could well be of any singer in history (New York Times 1973.) For others like myself, who recalled his capers, his faulty musicianship, his lack of discipline, and his dramatic flatness, Melchior's incomparable voice would forever be a prisoner of his incorrigible lack of artistry.

In 1931 as Melchior was abandoning Bayreuth, a young German colleague was rising to prominence.  Max Lorenz (1901-1975) replaced Melchior at Bayreuth in 1933, launching an international career that was to parallel Melchior's in chronology, longevity, and impact on the Heldentenor tradition. The travails of World War II took their toll on Lorenz and at the peak of his powers, his career ground to a halt, as Germany's cultural life lay in ruins. He was able, however, to do what few older singers of his wartime generation did: he made a post-war comeback and reaffirmed his Heldentenor stature. A more versatile artist than Melchior, he not only sang Tannhäuser, Rienzi, Siegmund, Siegfried, and Tristan, but also Herod (Salome), the Drum Major (Wozzeck,) and even in musicals at the Wiener Volksoper. Max Lorenz (1901-1975) replaced Melchior at Bayreuth in 1933, launching an international career that was to parallel Melchior's in chronology, longevity, and impact on the Heldentenor tradition. The travails of World War II took their toll on Lorenz and at the peak of his powers, his career ground to a halt, as Germany's cultural life lay in ruins. He was able, however, to do what few older singers of his wartime generation did: he made a post-war comeback and reaffirmed his Heldentenor stature. A more versatile artist than Melchior, he not only sang Tannhäuser, Rienzi, Siegmund, Siegfried, and Tristan, but also Herod (Salome), the Drum Major (Wozzeck,) and even in musicals at the Wiener Volksoper.

Lorenz was an echt Tenor with a large, bright, metal-edged, forwardly placed sound in the mold of Tichatschek and Slezak. He could thrust his voice over dense orchestrations with piercing radiance, and he could trumpet Siegfried's high Cs with ease. Occasionally gravelly with a strong vibrato, Lorenz's voice had a distinctive and emotive sound which Opernwelt (Der Heldentenor 1986) once described as "the expressionist among the great Wagner tenors." He was a master of nuancing, inflection, and subtle dynamics, and his keen sense of rubato (freedom of tempo) was keenly appreciated.

For Lorenz, the actor, the heroism of his characters derived not from the ease with which they defeated their obstacles, but from the tenacity with which they confronted their destiny. For Lorenz, the singer, much the same was true. Never was singing an effortless task as it was for Melchior, but never either was Lorenz defeated by its difficulties. He was the last of the giant sized echt Tenors, and he managed to preserve that strain in the 20th century tradition, becoming a respected teacher after his stage career had concluded. Moreover, he safeguarded the Heldentenor repertoire and race of singers through difficult social and artistic times in Europe.

In 1943 shortly before the war forced the closing of Bayreuth, a young tenor, Ludwig Suthaus (1906-1971), arrived there to sing Stolzing, and he returned again in 1951 to become Maestro Wilhelm Furtwängler's choice for the conductor's monumentally enduring recordings of Tristan and the Ring.  Suthaus possessed a large, dark, warm, poetically nuanced and dynamically varied instrument. He could create a satiny mezza voce at the same time that he could wield his voice with sharp thrust, and while the voice was not erotic in color, it had a tactile sensuality and fresh virility that gave it a youthful bloom. More than most of his contemporaries, Suthaus was a master of romantic cantabile; he stressed the melody while never losing incisiveness of text. He was capable of singing the long, achingly slow tempi that make Furtwängler's Tristan legendary. Critics agree, however, that he was a prosaic actor, and he never managed to deliver his roles from the two-dimensional realm of music and text to the three-dimensional one of living theatre. Suthaus possessed a large, dark, warm, poetically nuanced and dynamically varied instrument. He could create a satiny mezza voce at the same time that he could wield his voice with sharp thrust, and while the voice was not erotic in color, it had a tactile sensuality and fresh virility that gave it a youthful bloom. More than most of his contemporaries, Suthaus was a master of romantic cantabile; he stressed the melody while never losing incisiveness of text. He was capable of singing the long, achingly slow tempi that make Furtwängler's Tristan legendary. Critics agree, however, that he was a prosaic actor, and he never managed to deliver his roles from the two-dimensional realm of music and text to the three-dimensional one of living theatre.

Ludwig Suthaus possessed one of the purest voices of Heldentenor history. To the schwer Tenor tradition he brought greater vocal variety, shading, and poetry, as well as an almost symbiotic identity with the music. He achieved an organic oneness with the conductor and the composer's musical soul so that the breaths he drew seemed more than mere technical support for the singing, but rather the natural respiration of the music itself.

The post war years introduced a new generation of Heldentenors to Europe  and America. The Swedish born Karl Viktor "Set" Svanholm (1904-1964) dominated the decade of the fifties in the Wagner repertoire becoming the first of the great modern Heldentenor singing-actors. Like other schwer Tenors before him, he began as a baritone, but switched to tenor in 1936. He spent the war years in Sweden and then launched a post war international career that took him to the Met in 1946 where he was hailed as Melchior's successor. His final years were spent as the Intendant of the Royal Opera in Sweden where he brought the company into the modern age of theatre. and America. The Swedish born Karl Viktor "Set" Svanholm (1904-1964) dominated the decade of the fifties in the Wagner repertoire becoming the first of the great modern Heldentenor singing-actors. Like other schwer Tenors before him, he began as a baritone, but switched to tenor in 1936. He spent the war years in Sweden and then launched a post war international career that took him to the Met in 1946 where he was hailed as Melchior's successor. His final years were spent as the Intendant of the Royal Opera in Sweden where he brought the company into the modern age of theatre.

Listen to Set Svanholm: Siegfried/Wie end'ich die Furcht

Svanholm's voice was a majestic, expressive one; it had size, a clarion top, and what one critic called "strength, silver, and steel." He compensated for a somewhat gravelly tone and strong vibrato at the passaggio (register break) with his extraordinary ability to phrase, inflect words, and musically shape the subtleties of a role. Like Maria Callas, Svanholm was able to fuse words and sounds in a revelatory manner.

Not only was he an insightful musician, but he was a consummate actor. To see Svanholm on stage was to enjoy a singular experience in music-drama. Slim, tall, well-built, he combined athleticism with psychological intensity to deliver searing portrayals of heroes like Siegmund, Siegfried, and Tristan. Some critics like Harold Rosenthal found Svanholm's characterizations too cerebral, but for many, the tenor's ability to endow his heroes with both passion and brains gave his performances a memorable intensity and inner conviction. His heroes always existed on two planes: the façade of virile and classic heroism and the interior landscape of doubt, vulnerability, and softer human emotion.

Set Svanholm can be credited with being the first of the great Heldentenors to bring opera into the modern age of theatre. He established integrated standards for a new kind of music-drama that consisted of equal parts concentration on text, musical technique, and dramatic elements. He demonstrated that a voice not inherently beautiful could succeed magnificently with intelligence, cultivated musicianship, and complete artistry.

Svanholm's theatrical aesthetic that combined psychological interpretation with literary mythos helped usher in the new era of Heldentenor interpretation in which literal myth gave way to Freudian and existential realms in the New Bayreuth of Wieland Wagner, the composer's grandson whose theatrical genius forever changed the attitudes toward and look of the Meister's work. The preferred artist for this Bayreuth revolution was tenor Wolfgang Windgassen (1914-1974), who reigned at the Festspielhaus for almost two decades, one of the longest consecutive tenures of any major Heldentenor.

As a singing-actor, Windgassen epitomized the intellectual and psychological theatre that was the ideal of New Bayreuth, which stripped productions of the crippling realism that had characterized Cosima's style and introduced, instead, a minimalist, symbolist approach to décor inspired by the scenic artist Adolphe Appia. Raised in the intimacy of the German ensemble system, Windgassen felt most at home on European stages where he became a venerable presence.  Windgassen had a lyrical voice which was capable of heroic passion and sound, but one which he used with a lightness and restraint that became the basis for a distinctive new strain in Heldentenor singing. An echt Tenor in the Tichatschek-Slezak vein, Windgassen was something else his predecessors had not been; he was a leichter Held (a lighter voiced hero), whose singing style left its impact on all future generations of Heldentenors. Possessed of an extremely agile voice production, he sang with a bright, well-placed sound that replaced sheer decibels with thrilling projection. His dynamic control was exceptional; his diction was precise. He sang with a patina of rationality and technical precision that enveloped a core of psychological depth, and he consistently delivered high quality, committed performances throughout his career. Windgassen had a lyrical voice which was capable of heroic passion and sound, but one which he used with a lightness and restraint that became the basis for a distinctive new strain in Heldentenor singing. An echt Tenor in the Tichatschek-Slezak vein, Windgassen was something else his predecessors had not been; he was a leichter Held (a lighter voiced hero), whose singing style left its impact on all future generations of Heldentenors. Possessed of an extremely agile voice production, he sang with a bright, well-placed sound that replaced sheer decibels with thrilling projection. His dynamic control was exceptional; his diction was precise. He sang with a patina of rationality and technical precision that enveloped a core of psychological depth, and he consistently delivered high quality, committed performances throughout his career.

As an actor, Windgassen created characters from the interior outward. Coached in the economical plastic vocabulary of Wieland Wagner, Windgassen's acting relied on a symbolic stylization that had the heightened realism of a dream. Some found this approach static, but others saw his performances (and Wieland Wagner's directing) as brilliant exercises in naked truth.

Wolfgang Windgassen's legacy to the Heldentenor tradition is both musical and theatrical. Vocally, he helped to shape a new Heldentenor strain which embraced lyricism, and championed the lighter heroic voice. Dramatically, he incarnated a new, neo-classicist acting style whose primary focus was interior psychological motivation; he gave the Heldentenor tradition a new vocabulary of movement and gesture that in its simplicity and purity forced a re-evaluation of all stage demeanor that had preceded it. Windgassen was a prime mover in the theatrical vanguard which transformed opera into the producer's theatre it is today and which championed not only the ideal of ensemble theatre but also the Wagnerian faith in total music-drama.

Photos: Public Domain and from Carla Maria Verdino-S√ľllwold's book

We Need a Hero!: Heldentenors from Wagner's Time to the Present, a Critical History/Weiala Press

This article is in two parts. You have just read Part One.

To read Part Two, Click Here.

|

|