|

Simulcast operas are the fashion of the day. The trend setter, “HD Live at the Met,” started last season with seven superbly produced operas. Once again, this fall, at 1 pm New York time, when the curtain rises at Sunday matinees, audiences all over America and beyond can join in at their local cinema. For about $20 a ticket, some 600 movie theaters in the States offer the Met opera performances live, with easy-to-read subtitles, to be enjoyed from a prime “orchestra” seat. The success of the first season was such that San Francisco Opera quickly jumped on the bandwagon with its own series which, however, is not live but edited and canned. Still, San Franciscans have the option to brave wind and fog and watch an occasional live opera on a giant screen in a sports stadium: 23,000 people saw Nathalie Dessay in Lucia di Lammermoor (reviewed in these pages in August, 2008) at the AT&T ballpark. For “Live at the Met,” locals like me can drive half an hour north to the little Marin County town of Larkspur and comfortably settle into the old Lark Theater. What you get there is a big, packed cinema, an excellent screen and sound, decent coffee and delicious free-of-charge muffins. When there is a Met gala the friendly volunteers serve champagne. And yes, popcorn is an option, too.

By now the new fashion has spread to Europe and you can catch operas from La Scala, Salzburg and other European venues at a cinema near you, with Bayreuth and the London Royal Opera waiting in the wings. None of these are live, of course. La Scala, for example, offers the same fare as is available on DVDs, with the one advantage of the big screen.

On October 12, the second season of “Live at the Met” started with fanfare. Finnish soprano Karita Mattila burned the stage as Salome, the perverse biblical princess, in the 1905 opera Salome by Richard Strauss. Mattila is one of the most accomplished actresses among dramatic sopranos of our time and her Salome (a recap from 2004, when she sang the role at the Met for the first time) once again brought the house down with a “dream performance” (The New Yorker).

The opera follows the stage play by Oscar Wilde (in a strikingly poetic German translation of the play which Wilde wrote for Sarah Bernhardt… in French!). Strauss had seen the play at Max Reinhardt’s Kleines Theater in Berlin, in 1902. In his Recollections and Reflections, he recalls that after the performance someone suggested, “’Strauss, surely that’s an opera subject for you!’ I was able to tell him truthfully: ‘I’m already composing.’” This work, which marks the beginning of modern music in opera, demands extreme athleticism of the singer’s vocal chords because of the consistent high tessitura. Moreover, there is the notorious “dance of the seven veils,” a seven-minute-long stumble-stone for most divas who take on this tricky role. The ideal Salome, according to Strauss, is “a sixteen-year-old with the voice of Isolde” – but such a Lolita with a Wagnerian vocal volume who can dance and strip naked has been a rare find during the past 100 years. The usual gamble is: you either get a voice or a body. The first-ever Salome daring to appear naked at the fall of the seventh veil, Anja Silja, in 1968, had the body of a twenty-something but is rumored to have ruined her voice with the role. The very young, beautiful Teresa Stratas created a memorably demented Salome in 1974 (available on video) but her rolling on the floor in her dance makes one want to look away as if it were road-kill. Singers who had the looks – like Maria Ewing (also on video) – and singers who had the voice – like the colossal Montserrat Caballe (to be beheld on YouTube) – went from the sublime straight to the ridiculous in their seven-veil ordeal.

In fact, only a very mature voice can successfully tackle the extended high notes of Salome’s ecstatic ravings. A voice like Karita Mattila’s – a strong-muscled, beautiful and radiant voice with a pearly sheen and a capacity to pierce through a huge orchestral din without ever getting strained and shrill. Mattila, at the height of a world career, is 48. She is in famously good shape. Last season, during an intermission of Puccini’s Manon, the camera showed her warming up by happily going into a split right backstage between the set decorations of the Met. One likes to look at her face when she is singing, a pleasure you don’t take for granted on the opera stage, and she is still slender in a voluptuous way. But a 16-year-old Lolita? One has to see it to believe it, and I hope the opera will be released on DVD so others can see it, too.

Before the curtain goes up, the cameras are already backstage. Opera star Deborah Voigt knocks at the door of Karita Mattila’s loge, looking radiant after what seems to be the loss of another 100 pounds. Charmingly, she wonders if Karita might have “Something to say to the audience?” The door opens, the diva comes out: “Here’s something I always like to say: let’s kick ass!”  It’s one of those moments the filmed Met productions are famous for: you get to peek behind the curtains and closed doors as if you were part of the event, watching and talking to the stars and the technicians before the show and between the acts. It’s done every time with style and in a good-humored spirit of sharing the excitement of a live performance. It’s one of those moments the filmed Met productions are famous for: you get to peek behind the curtains and closed doors as if you were part of the event, watching and talking to the stars and the technicians before the show and between the acts. It’s done every time with style and in a good-humored spirit of sharing the excitement of a live performance.

Barefoot, her blond hair in nonchalant curls, hardly made up, in a slinky pearl-colored evening gown, Mattila walks toward the stage, loosens her jaw and looks like an athlete ready for the ring. There is not an ounce of artificialness, self-consciousness or make-believe in her demeanor. This is the Mattila-effect: she gives herself to the viewers and, in the next moment, to the performance with no holds barred. She is simply 100 percent “real”.

Renowned director Jürgen Flimm has staged the opera with very simple means in a modern setting. No fuss, no folklore, no palatial crowds. One side of the stage set is a gawdy, Vegas-style interior palace wall, the other an architectural rendering of the desert hills that let the winds of divine vengeance roar in at the end, after Salome has stripped for Herod, her incestuous step-father, and kissed (at length) the decapitated head of John the Baptist. There is no moon, no romance. Nothing to distract from the elementary force of the drama with its determined focus on Salome. The whole action happens in full light and transparency on a glass platform and comes across that much more violently modern and shocking.

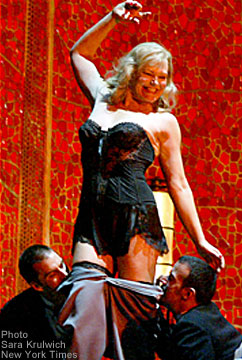

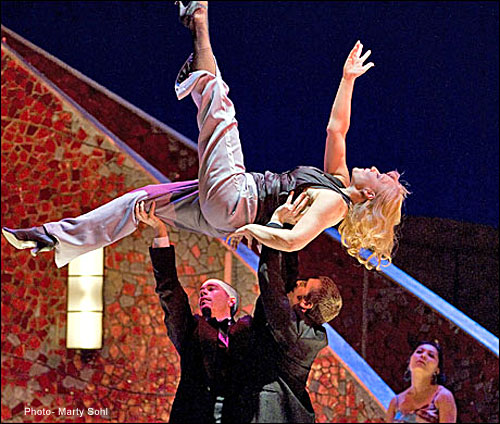

Mattila gets every emotion right: Salome’s smoldering moodiness, boredom, the rage and hatred of a young princess who grew up with the drunken debauchery of Herod’s court. There is a strong suggestion that Salome is a sexually abused and therefore oversexed girl who holds the power over a lecherous king and fully enjoys this power. There is, however, also the confusing innocence of youth, and the spoiled princess is troubled and undone by her violent yearning for the unfathomable, unfulfillable love – perhaps a spiritual form of love -- that the prophet shows her while he rejects the sexual seduction which is all she knows and controls. In Mattila’s interpretation Salome knows only too well what to do to “have” him in spite of him. When the dance begins she appears in a tuxedo, à la Marlene Dietrich in Marocco. Helped by an intelligent choreographer (Doug Varone) she flirts with the king while she makes out with two courtiers. She throws Herod her clothes as she sheds them and even teases him with a lap dance. Having been objectified by his lust, she relishes every moment of her sly seduction to reduce him to being an object, the object of her will, her fury.

It is rare on any stage to see a frank embodiment of a woman’s sexuality, free of the stereotypical make-believe we are used to from Hollywood and pornography. In Mattila’s interpretation, Salome’s unhinged desire and violent ambivalence are not another cliché of female “hysteria,” they are feelings that make sense; they are transparent, real.  The question of the performer’s age does not even arise with such fearless nakedness of emotional extremes. The New York Observer wrote, “Matching her own beautifully crazed movements with every bar of Strauss' beautifully crazed music, she brought herself to a state of physical and vocal ecstasy that was so powerfully sustained as to make us complicit in the character's madness.” The question of the performer’s age does not even arise with such fearless nakedness of emotional extremes. The New York Observer wrote, “Matching her own beautifully crazed movements with every bar of Strauss' beautifully crazed music, she brought herself to a state of physical and vocal ecstasy that was so powerfully sustained as to make us complicit in the character's madness.”

A lot of this success has to do with the competent staging and the welcome restraint Jürgen Flimm showed in the direction of the other main players. Finnish baritone Juha Uusitalo was an adequate John the Baptist (Jochanaan); Kim Begley and Ildiko Komlosi impressed as a mellow Herod and sexy Herodias who, in this production, were not cartoonish monsters or clowns but “real”, modern people like Salome herself.

Oddly, the unflinching truthfulness of this simulcast stopped at the moment of physical nakedness. Simulcast viewers were treated like TV families at home who had to be protected from another case of “wardrobe malfunction.” The cameras panned away… Is the 16-year-old biblical heroine considered too advanced for the infantilized American audiences of 2008? The same audiences who might go looking for some “Freedom fries” with their hot dog at intermission?

It will be interesting to see if the second season repeats the flawless first. I fear the worst for the Met’s attempts at John Adams’s Doctor Atomic and Puccini’s La Rondine which were recently shown at San Francisco Opera. They both tanked due to the vapid libretti and weak music. (I reviewed Doctor Atomic for Scene4 and added a persiflage, “Alice Alice”, in April 2006.) In the cinecast of La Rondine, the singers did not manage a single genuine emotion for the close-ups of the cameras. The worst contender was Angela Gheorghiu and the comparison here will be telling as she is going to sing the same role in the Met production.

Highlights to look forward to are seeing Anna Netrebko again. Last season she was Juliet in Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet, causing highschool students to venture into opera because of her movie star looks. She is picking up Nathalie Dessay’s part in Lucia di Lammermoor while Nathalie Dessay takes on Bellini’s La Somnambula. Renée Fleming and Thomas Hampson will sing Massenet’s Thais. Acclaimed theater director Robert Lepage creates a new production of La Damnation de Faust (Berlioz) while choreographer Mark Morris repeats his acclaimed Orfeo ed Euridice by Gluck. Late film director Anthony Minghella’s first and last opera staging, Puccini’s Madama Butterfly from 2006, will be performed again.

More about the series can be found online.

Cover Photo - Marty Sohl

|