|

Cal Performances on the Berkeley campus has created another buzz in the world of dance. On one of only two stops in the U.S. (the other one being L.A.), the most famous French ballerina Sylvie Guillem appeared in a duo performance with the London-born Bengali dance star Akram Khan. The two dancers from opposite classical traditions consider their collaboration more than a hybrid or fusion between East and West. Their new 70-minute piece, according to the program, is a "journey to unexplored dance territory", and according to the London Daily Telegraph, "takes your breath away."

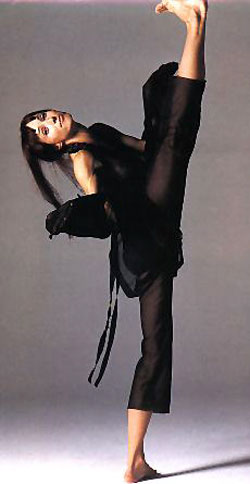

Sylvie Guillem has most of the attributes that make a ballerina famous: the fluidity and ease of movement, the grace of her neck, the beauty of her body, the feather-like lightness of her arms and hands, her airborne balances, the quicksilver speed of her leaps and bounds. But if Guillem lacks the natural facial expressivity, she makes up for it with the expressivity and beauty of her feet.

Sylvie Guillem's feet function like hands attached to legs. They turn the common repertoire of classical leg movements into something akin to a wondrous, sensuous adventure. In addition, those feet of hers rise like wings above her head into easy 180 degree extensions in any position. Guillem manages to stand on her toes and, without any male (or other) support,  unfold her other leg like a flower petal: the leg goes up at her side and, leisurely, moves past her ear into the thin air above. Apart from certain Chinese circus acrobats, there is no one in her generation of dancers (she is 41) who can do anything like it. Sylvie can do it because she was already a Wunderkind as a child gymnast, training for the Olympics, before the Opera Ballet in Paris snatched her up. It didn't hurt that the French nymph was pretty, had a perfectly proportioned body with slender long limbs, and commanded extraordinary energy, speed and balance. It did not take long for her to be noticed by Rudolf Nureyev, then artistic director of the Paris Opera Ballet. He led the 17-year-old dancer in a quick rise to the positions of soloist and, at age 19, to the very top -- the prima ballerina or étoile. Choreographers like Béjart, Karole Armitage, Wiilliam Forsythe, John Neumeier, Jerome Robbins or Robert Wilson soon stood in line to work with her. But when Nureyev wanted to keep tight reins over his protégée she „eloped" across the French borders. Not unlike Nureyev himself, who had eloped from Soviet ballet constraints, Guillem did not care about creating a "national catastrophe" (Le Monde) that was even discussed within the government. She was determined to take control of her own artistic evolution, to dance wherever and with whomever she liked. unfold her other leg like a flower petal: the leg goes up at her side and, leisurely, moves past her ear into the thin air above. Apart from certain Chinese circus acrobats, there is no one in her generation of dancers (she is 41) who can do anything like it. Sylvie can do it because she was already a Wunderkind as a child gymnast, training for the Olympics, before the Opera Ballet in Paris snatched her up. It didn't hurt that the French nymph was pretty, had a perfectly proportioned body with slender long limbs, and commanded extraordinary energy, speed and balance. It did not take long for her to be noticed by Rudolf Nureyev, then artistic director of the Paris Opera Ballet. He led the 17-year-old dancer in a quick rise to the positions of soloist and, at age 19, to the very top -- the prima ballerina or étoile. Choreographers like Béjart, Karole Armitage, Wiilliam Forsythe, John Neumeier, Jerome Robbins or Robert Wilson soon stood in line to work with her. But when Nureyev wanted to keep tight reins over his protégée she „eloped" across the French borders. Not unlike Nureyev himself, who had eloped from Soviet ballet constraints, Guillem did not care about creating a "national catastrophe" (Le Monde) that was even discussed within the government. She was determined to take control of her own artistic evolution, to dance wherever and with whomever she liked.

For the next 17 years she became the controversial darling of the Royal Ballet in London, but controlling her roles as well as the choice of her partners proved still not enough. Sadler's Wells finally offered her the freedom to branch out ad libitum into modern and experimental dance. In the last few years she did stints with the Ballet Boyz, Wayne McGregor, and repeatedly collaborated with Russell Maliphant.

Before I get to her latest experiment with dancer and choreographer Akram Khan, a word needs to be said about the controversy.

Guillem's legs did not please all of her stiff-upper-lip British ballet audiences. Their extensions were considered unnatural, inhumane, shocking and even perversely vulgar. According to some critics, those legs did not belong in classical ballet. Those legs, however, had single-handedly (!) brought excitement onto the ballet stage -- a fact most aptly recognized by William Forsythe who wrote one of the most extraordinarily difficult and thrilling parts for her in 1987. Captured in a TV documentary, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated is an abstract dance piece that demands the impossible in terms of twists, off-balances, speed attacks and flash-like extensions – all of which she delivered with unearthly ease and a relaxed face.

Anybody interested can see excerpts from this and many other parts and roles on-line, on YouTube. The most sensational excerpt is not Forsythe's Herman Schmerman with her see-through top, but a study posted by Vale Bjork called "Sylvie Guillem" that shows, on a black stage, with prayer-like concentration, the erotic power of her leg and foot work. In all the excerpts, her superior technique is instantly apparent, and also, perhaps, the fact that she is not particularly warm or gifted for acting. That's what made her Forsythe parts so convincing: her thoroughly cool, disengaged air of modernity.

Guillem made only one appearance, to my knowledge, in San Francisco, in the nineties. She guest-starred in La Bayadère – one of those insufferable 19th century ballet hams that one has better avoid unless a soloist of "inhumane" capacities brings a sudden interest to the dusty affair. The dancing of Guillem in the midst of a "normal" company was like the appearance of a space alien among mere mortals who eyed the tense and anorexic-looking superstar with visible dismay. This, already, was the "monstre sacré" (as the French call a prodigiously gifted and monstrously eccentric celebrity) who had rumors flying about her caprices at the Royal Ballet, about her "demandingness" and determination to stand apart and do as she pleased. It pleased her, for example, to alter her costumes and steps to suit herself, and to refuse interviews. In short, "Mademoiselle Non", as she was nicknamed, claimed the right to be the superstar she was—no different than an Eleanore Duse, Sarah Bernhardt, Maria Callas or Cecilia Bartoli, artists who demand something in return for the extraordinary art they deliver. In Guillem's own words: "I am difficult wth myself, so I have the right to be difficult with others."

I am not sure about the mix of calculation and self-irony that inspired Guillem to call her duet with Akram Khan Sacred Monsters (Monstres Sacrés). The two superstars present themselves with utmost understatement as mere humans, just dancers pretending to do nothing more than have a little fun together. Which is, of course, a contradiction in itself: only stars who have something extraordinary to offer can come up with such a pretense and sell it to audiences worldwide. A case in point is the stunning stage set. At first, in dim lighting, Guillem, Khan and their five musicians onstage seem placed in a stark desert landscape that fills the whole stage with diagonal sand drifts arranged around a black horizontal gap. When the backdrop lights up the landscape seems to harden into a glacier with a dangerous crack across its length, and in the end, the full blast of light reveals the crumpled strips of paper it is all made up of.

I am not a connoisseur of Indian dance, so I can't judge Khan's ways of pushing the envelope of classical Kathak dancing, I can only say that he is a charismatic, warm performer who danced with an almost feminine suppleness of arm movements that contrasted and contrapunkted beautifully with his elaborate staccato stomping leg work (partly supported by ankle bells.) He has a strong, well-rooted and slightly stocky body and yet adapted perfectly to his beanstalk partner who is taller -- even without any use of toe shoes.

|

It took about 10 minutes of small-motion teases before Guillem let loose in a solo (choreographed in part by Lin Hwai-min, the director of the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan ) and reminded us of a few "monstrous" things she can do with her body: gymnast acrobatics, one or two of those ear-scraping leg lifts, humorous off-balance twists, a few virtiginous back-bends, martial arts kicks and gazelle-light speeds. However, the focus here is on "a few". Guillem held back, her mastery in this entire solo/duo performance was displayed in mostly small ways, intricacies, as if to say, Well, you all know and have seen enough of my salto mortales, now watch me do what you could almost do yourselves. Sure, let's get right ahead. But what are we to do with our nostalgia for the sensational, breathtaking, superhuman Sylvie Guillem of her classical years?

A lot of time between solos and duets is spent talking – obviously another new challenge the notoriously experimental, but shy and mute Guillem has forced herself into. In the fashion of "He says she says" they chat about each other's idiosyncrasies and foibles: "Will she follow the rules?", "Is this right?" They politely watch each other's solos, standing back, Guillem sitting like in a dance studio, drinking from a water bottle and braiding her henna-red hair. Khan deplores the baldness that mocks his boyhood dream of being Krishna: instead of being the god he is only a human monster. As a reward for that confession, he gets a friendly tap on his head by Guillem with the half tender, half dry comment "You are a beautiful boy." At one point, the two seem to comment on the nonsense of their talking when Guillem replies to Khan's heavily accented English in soothing, cooing Italian. They do all this admirably well, considering. Considering what exactly? Considering how far this takes them from their home base. But when the masters of such a game come to mind, Laurie Anderson, say, or Pina Bausch's and William Forsythe's talking dancers, it seems a bit self-conscious and leaves a lot to wish for.

Elements of childhood tug-of-war and strength competitions turn into stop-start mirror games that owe a lot to action-reaction improv techniques and at their best, remind one of experimental theater like Robert Wilson's Black Rider with its stylized wood-puppet moves, or London's Theatre de Complicité with Shockheaded Peter's extreme marionette disjointments. Another duet (all of the duets choreographed by Khan) is about flirting and chasing and power games that always lead to equality and balance (enhanced by the fact that both dancers are dressed in the same Japanese warrior pants and matching T-shirts). A series of mirror moves is a refined version of improv basics, another piece is a simple, but effective exploration of what two dancers can do without letting go of each other's hands. The final duet has Guillem wrapped around Khan's waist and body so tightly that the figure of a four-armed Shiva appears – Indian/modern dance meets Shen Wei. Guillem has tried this kind of experimental mix of styles in similar collaborations with Russell Maliphant, but classical and modern dance are closer cousins. Wedding East and West dance styles in this way may create a certain vision of a new "World dance" style. At the same time it could be seen as a heady caprice, similar to, say, setting a diamond in fine wood.

Accompanied by a group of five excellent world music instrumentalists and singers (cellist Phillip Sheppard among them), the understatement of the Sacred Monsters worked its strange charm – not exactly exciting, but very stylish.

Cover Photo - Tristram Kenton

|

|