|

What is the one most influential American opera premiered in the past 100 years? This writer doesn't know and suspects no musicologist would have a ready answer, let alone a studied short list of candidates. And what opera critic has seen all the new operas to make such a claim? (After all, not many new American operas have commercially available recordings.) As I have discovered in the past by interviewing a set of five composers, including prominently known Mark Adamo and Deborah Drattell, separating American opera from all other new opera may not entail anything more than the opera composer being entitled to or holding a passport from the United States. And this is the definition of American opera according to Virgil Thomson. That said, this writer chooses to exclude the German-born Kurt Weill and the Russian-born Igor Stravinsky, who both became American citizens late in their artistic careers.

DROWNING IN THE DEEP END: 100 YEARS AGO IN AMERICAN OPERA

The next question then is what does the pool of contemporary opera since 1909 include? Drawing from USOpera.com, a website that offers a chronological list of American opera that spans from 1841 to 1995, one notices mention in 1909 of a musical play and in 1908 a comic opera (Cap'n Kidd & Co) by Deems Taylor (1885-1966). Taylor's The King's Henchman with libretto by Edna St. Vincent Millay received its world premiere February 17, 1927, at the Metropolitan Opera, which tapped Taylor to produce its first commissioned work. The 17 performances of that premiere production set a record for an American opera. Peter Ibbetson, his second Met commission, premiered in 1933, and according to The New York Times critic John Rockwell writing a book review of a biography on Taylor ("Practicing What He Preached" December 7, 2003, NY Times), Ibbetson "racked up 22 Met performances." Taylor, who also worked as an influential music critic, was a prolific and popular composer in his time, but according to USOpera.com, Taylor's "works never impressed critics and shortly after his death they dropped from the public's memory." Placing Taylor in profile with his contemporaries, John Rockwell wrote in the book review previously mentioned:

"Taylor basked in the glory of the moment, though his music was less of his moment than of the recent past, prone to tidy late-Romantic, quasi-Impressionist musings laced with comfortable folk tunes. He recognized an inherently derivative quality in his music, for all its craft: ''Nothing that hasn't been said a million times,'' he lamented about one of his works.

"However much his music appealed to middlebrow listeners and organizations like the Met, it seemed old-fashioned to progressive composers and critics. American modernist composers, for all their diversity (Roger Sessions's Germanic dissonance versus Aaron Copland's Francophile populism versus Virgil Thomson's quirky abstraction), promoted themselves as a group. Taylor, in Pegolotti's account, was an emotionally repressed loner in his social and romantic life as well as in his contacts with fellow composers. If they were Ivy Leaguers, he was New York University. If they studied with Nadia Boulanger, he studied for a few months with crusty old Oscar Coon. Furthermore, and this meant something, Taylor was enthusiastically heterosexual when a large number of the most influential American composers were homosexual."

WHO LEARNED TO SWIM WITH ATONALIST ROGER SESSIONS

In 1910, Roger Sessions (1896-1985) premiered Lancelot and Elaine, his first of five operas (though two were not finished). His opera Montezuma (premiered in 1964) is ranked with three of the best known 12-tone operas: Alban Berg's Wozzeck (1925) and Lulu (1937) and with Arnold Schoenberg's Erwartung (1924). Although none of his operas attained status in opera repertory, his highly original music which ranges from Germanic influences to 12-tone serialism and much more is well respected and through his long teaching career at Princeton and University of California, Berkeley, he taught such prominent composers as John Adams, Milton Babbitt, David Del Tredici, and John Harbison.

WHO GOT STUCK ON DRY LAND: AARON COPLAND

For all of Aaron Copland's (1900-1990) profound influence on American classical music, he managed to write only one opera that has had occasional productions. The Tender Land premiered at New York City Opera in 1954. Written originally for the intimacy of an NBC Television Opera Workshop, but never getting its promised airing, Copland's opera did not present well in the much larger NYCO theater. Writing for The New York Times ("Music: Copland Conducts" July 29, 1965) Howard Klein said, "Tender Land is closer to Oklahoma [the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical and Rodgers and Hammerstein were the commissioners of The Tender Land] than it is to Wozzeck." Most critics of Copland's time found Tender Land lyrically pleasing and very American, but not dramatically interesting. Nevertheless, the opera deservingly has entered opera repertory.

WHO ROCKED THE BOAT: MARC BLITZSTEIN

Another American composer who was taught by Nada Boulanger as well as Arnold Schoenberg is Marc Blitzstein (1905-1964). A prolific composer for theater who died from injuries sustained possibly in a gay-bashing incident on the Caribbean island of Martinique, he is best known for his music theater work The Cradle Will Rock (premiered in 1937) that mixes opera and popular music styles.

WHAT STILL FLOATS: FOUR SAINTS IN THREE ACTS

With this mini survey of the American opera scene in mind, Four Saints in Three Acts by Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) based on a libretto by Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) stands apart from other American operas. To this day, its February 20, 1934, Broadway premiere saw a remarkable 60-performance run, something that no other American opera has achieved. Many music scholars also point to Four Saints as the beginning of mature American opera as distinguished from European opera. Unlike traditional opera, Four Saints is not a narrative story. Stein's libretto is focused on the vitality of the words selected and how these words might engage the attention of audience members. Thomson's handling of Stein's libretto is extraordinarily sensitive to the great modernist's intentions. For example, Thomson created two additional characters (the Commère and the Compère) to sing Stein's stage directions, which in Stein's highly experimental theater palette was essential to her overall intention.

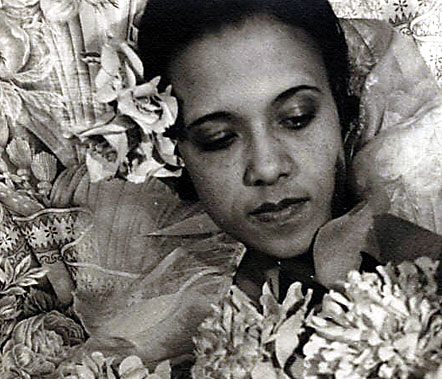

|

With a run time of just under one hour and a half, this opera that reflects the music of the composer's Baptist upbringing is sung by two sopranos, two mezzos, two tenors, one baritone, two basses along with a sizeable chorus. In keeping with the exceptional original production, the cast of singers is black though the story of the opera has nothing to do with black life. (For example, George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, which premiered October 10, 1935, after Four Saints, uses a black cast and the story concerns black culture set in and around Charleston, South Carolina.) Also Maurice Grosser who created the original overall conception for how the opera would work on stage (he organized Stein's untidy libretto into tableaux] cautioned in his program notes that a director need not adhere to a black cast. Still, Stein mentions "negro'' in her libretto.

St. Teresa I

Could a negro be be with a beard

St. Teresa II

To see and to be.

St. Teresa I

Never to have seen a negro with it there

[from Act I, end of Tableau III of Four Saints in Three Acts]

What worked for Virgil Thomson was that he found the black singers available to him to have exceptionally good diction and volume projection. Also, he noted that the black singers fully accepted Stein's text, making it easy for everyone to proceed.

In many ways, Four Saints, a joyful opera that premiered during the Great Depression, may be coming into a time when audiences can more fully appreciate what the collaboration of Stein's words married to Thomson music offers. First, let me talk about how to describe what Stein wrote. Using a landscape (Stein specifically used the word landscape to describe this work) filled with saints, Stein explores the artist at work. And literally you hear Stein at work:

Tenors & Basses (Chorus I)

A narrative who do who does. A narrative to plan an opera.

[from the Prologue of Four Saints in Three Acts]

THE LANDSCAPE OF FOUR SAINTS

There are four principle saints: Saint Teresa of Avila, Saint Ignatius Loyola, and their respective (but fictional) confidents Saint Settlement and Saint Chavez. Thomas added a second Saint Teresa to accommodate musical duets. Also there are many other named and unnamed saints who comprise small and larger choruses. Without overt correspondence, the saints stand in for such artists as Stein's Spanish-born friends Pablo Picasso and Juan Gris. The saints, especially Teresa, can be thought of as the author herself and her life-long partner Alice B. Toklas, who Stein nicknamed Thérèse after, in 1912, the couple visited a church in Avila, Spain, dedicated to St. Teresa. In fact, Stein's original libretto used the French spelling Thérèse, but Thomson preferred the extra syllable and got her permission to make the name Teresa.

|

According to Steven Watson in his book Prepare for Saints: Gertrude Stein, Virgil Thomson, and the Mainstreaming of American Modernism (p. 49), Thomson's intent was to do justice in setting the spoken American language to music, something that had been attempted as early as the 1700s by George Frederic Handel, but had not been done successfully in opera before Four Saints. In preparation for working with Stein's text, Thomson also studied liturgical chants tied to the rhythms of Latin. For Stein, who was a secular Jew, the spiritual (religious) nature of saints equated to the creative impulse in the artist. In the words of Bonnie Marranca in her essay "St. Gertrude" published in Ecologies of Theater, "Stein was preoccupied by creation, not representation."

THE HIPNESS OF FRACTURED TIME, LOGIC, AND THE FOURTH WALL

So, back to the new appreciation current audiences might have for Four Saints. Audiences today have become familiar with works in other genres that fracture time and expected logic. In film, two widely available works that deal with fractured time and logic are Charlie Kaufman's Being John Malkovich (1999) and Michel Gondry's Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004). Stein's fracturing of time and logic is still unusual. Mainly, she upsets the structure of her work. The title declares Four Saints in Three Acts. What we are given are many more than four saints in four acts. Throughout the acts, questions arise about how many saints, how many acts, and how much of it [Stein lets the audience answer what "it" is] is finished.

Audiences today are also familiar with theatrical and film works that breach the fourth wall so that characters talk directly to the audience or narrate in some way that makes the audience aware that they are experiencing a play or a film. An example in a Broadway musical is John Kander's Cabaret and in film is Woody Allen's Annie Hall. With Stein aided by Thomson, the person seated in the audience is face-to-face with the author. Thomson's use of the narrating characters—the Commère and the Compère, stock characters in French burlesque—provide Stein's running commentary on stage directions.

COLLECTING STEIN'S DRIFTWOOD

The process of interacting with the audience is Stein's intention. She had no interest in hypnotizing with a story. What was habitual in theater, Stein sidestepped in the interest of waking up the viewer/listener's senses. To arouse her audience, Stein populated her text about saints set in sixteenth-century Spain with surprising found objects such as the opening line to the American patriotic song "My Country, 'Tis of Thee" (Thomson, of course, quotes the music and then blends it back into his musical frame) and a riff on April Fool's Day. Current day audiences might be surprised to hear lines like these that might suggest advocacy for the Green movement, technological advancements, and racism: "Planting it green means that it is protected from the sun and from the wind…" or "Saint Teresa could be photographed and then they talking out her had changed it to a nun" or "If it were possible to kill five thousand Chinamen by pressing a button would it be done."

So what does one make of such phrases as "Four saints prepare for saints it make it well well fish," "pigeons on the grass, alas," and "how many doors are in it"? Underpinning what seems to be nursery rhyme and chaotic detritus that float around and through key concepts involving saints, spirituality, and every day symbols like windows, doors, eggs, birds, and trees is Stein's masterful strategy based on what she learned from her Harvard professor William James, the psychologist whose vast teachings about the mind and body laid the groundwork in modernist literature and art for what's known as the stream of consciousness. The answer to why phrases of Stein's ordinary words set to Thomson's seemingly unsophisticated tonal music burrow deeply into a listener's memory lies in Stein's mastery of what James taught.

WHAT GOES AROUND COMES AROUND

Going back to the musical environment of Thomson's time, he with his tonal approach, along with Aaron Copland and Marc Blitzstein, stood in opposition to dissonant composition (such as the work of Roger Sessions) which, in the classical music world until the early 1990s, was considered the serious innovative approach to classical composition. To this writer's way of thinking, the so-called minimalist composers such as Philip Glass, Michael Nyman, Steve Reich, and Terry Riley bridged the gap between tonal and atonal classical work. Called a post-minimalist and influenced at various times by such composers as Schoenberg, Philip Glass, and John Cage, John Adams, particularly with his last opera Doctor Atomic, has moved into new musical territory. In Hallelujah Junction: Composing an American Life, Adams's memoir published in 2008, Adams offered this epiphany that came out of hearing composer/conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen answer a question concerning tonal harmony, "I began to confirm a suspicion that I'd had for a very long time, that atonality rather than enriching the expressive palette of the composer, in fact did just the opposite. When I surveyed the music of other cultures both geographically and historically, nowhere could I find a coherent, meaningful musical system that wasn't tonal in its root."

Now, which composers and librettists have been influenced byFour Saints in Three Acts? This writer will hedge and say she is not entirely sure that anyone can give a definitive list, because she believes that the effect of Four Saints is subtle, if not, subterranean. With no fixed point of influence, who comes to mind for this writer are George Gershwin (Porgy and Bess, 1935), Dominick Argento (Postcard from Morocco, 1971), Philip Glass and Robert Wilson (Einstein on the Beach, 1976), Scott Wheeler (Democracy: An American Comedy, 2005), and Ned Rorem and J. D. McClatchy, (Our Town, 2006). Also include in this list Leonard Bernstein, Paul Bowles, and John Cage.

Having just experienced (December 12, 2008, at the Walker Art Center's McGuire Theater in Minneapolis) composer Anthony Gatto's and director Jay Scheib's premiere of The Making of Americans, an emotionally moving cross-media chamber opera based on Gertrude Stein's seminal novel by the same title, this writer has yet to ascertain the influence of Four Saints on this particular work which will be reviewed in the February 2009 issue of Scene4 Magazine. The point is that Four Saints in Three Acts will continue to influence new operatic works.

Mark your calendar now for February 20, 2009, to see the 50-minute version of Four Saints in Three Acts by Nancy Rhodes and Encompass New Opera Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center in the 75th anniversary celebration of the 1934 Broadway premiere of this seminal opera.

Photos - Yale Collection of American Literature,

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

|