|

Every now and then there is a new reason to fall in love with San Francisco. This time it's the advancing project of a new San Francisco Opera Ring cycle. After the first part, Wagner's "prologue" Das Rheingold in 2008, now the curtain went up on part two, Die Walküre, one of the three 4½ to 5-hour mammoths of the cycle that are to follow next summer when the entire Ring des Nibelungen will be performed in Bayreuth fashion, one whole cycle per week.

To celebrate the occasion, the opera arranged a costume contest: any opera buff was invited to show up as one of the characters – Gods, Giants, Valkyries, etc. On a sunny, balmy morning before a Walküre matinee, the group of finalists waited for the verdict and posed for the cameras — a beautiful Hawaiian "Erda" took away the second prize. The winner, however, was not the deserving black poodle with a white Wotan eye-patch and toy spear, but a conceptual costume: the Eco (Echo?)-Feminist — a man (or was it a woman?) with green sword and "Save the Planet" shopping bags, claiming to represent the spirit of this new Ring production.

Could it get any more San Francisco?

|

But eco-feminism was not the intended message of this Ring. In my review of Das Rheingold (San Francisco Opera's "Summer of Madness," August 2008) I pointed out that "prolific American director Francesca Zambello's intention is to create 'the American Ring,' to find places where 'American images meet Wagnerian mythology'. A tempting idea — after the countless interpretative modern stagings in recent decades that set the Ring anywhere in either post-atomic or other sci-fi landscapes, in totalitarian regimes or simply in today's market-driven computer age." Zambello's Rheingold two years ago, was touch and go with its somewhat forced Gold Rush Americana (Alberich as gold-digger, the Gods as banal robber-barons) and mixed success of casting, but this time the director has hit her target with a fabulous, well thought-out production that has almost everything one could wish for. It even has American relevance to the degree that one could say: if the next two sections hold up this level of creativity and congruity, Zambello has indeed pulled off the Great All-American Ring.

|

Of course, Die Walküre makes it comparatively easy. It's the most dramatically daring and intriguing and therefore the most often performed part of the quartet. But it's nevertheless rare to see a truly thrilling Walküre,not to mention one that can stand up to French theater director Patrice Chéreau's until now incomparable Bayreuth 1976 anniversary production (with Pierre Boulez at the helm, available on DVD and also in the form of a fascinating book). Chéreau, like it or not, has set the standard of modern relevance, mythical grandeur and psychological penetration that every new Ring has to measure up to. Zambello's Walküre comes amazingly close with a superb cast of singers who are also (mostly) excellent actors, under the energetic baton of former San Francisco Opera music director Donald Ronnicles, with stunning sets, dramatic video technology and pyrotechnics. But most importantly, she has come up with exciting interpretive ideas and an ideal Brünnhilde – one could argue, the Brünnhilde for the 21st American century.

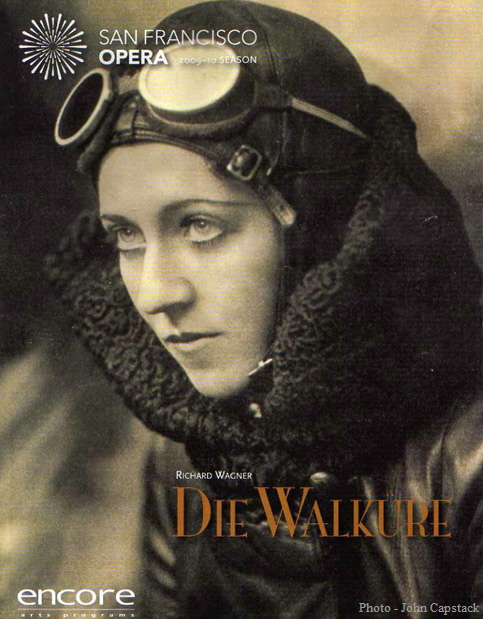

Zambello's Brünnhilde is the Valkyrie daughter of an industrial-age titan with a penthouse office that seems to be floating above the New York skyline like a cloud on top of some Mount Olympus. A boy-girl with a bobby pin in her short bob cut, she is dressed in pioneer aviator garb – a perfect incarnation of American modernism of the last century with all the right "over-tones" for today. Slender, agile Wagnerian soprano Nina Stemme, a Swedish superstar, embodies her as if she had just turned sweet sixteen in that Walhalla penthouse. Singing with an effortlessly clear, lyrical voice full of emotional shadings, Stemme's cocky, self-assured, fun-loving tomboy assumes it her birthright to be somewhat equal to Father Wotan. She fisty-cuffs him in mutual smirks over wifely Fricka (a majestic matron from Germany, Janina Baechle), puts her boots on his desk and picks up his phone to announce Fricka's ill-boding arrival. After toying with his spear like some Karate Kid with his Shaolin sword, she exits riding her dad piggy-back, shouting her jubilant "Hoia-to ho!" In short, she is Wotan's free-spirited, well-spoiled brat who can't ever do wrong. Until, of course, she does him wrong, and then all hell breaks loose.

|

When Brünnhilde comes face to face with Wotan's illegitimate son Siegmund, the all-consuming father love is forgotten and cast aside for her first adult stirrings. This crisis is staged in exactly the way Siegmund usually, in Act 1, falls in love with his lost twin sister Sieglinde: there is a palpable electric shock of recognition in Brünnhilde and an instant awakening to passion. The fact that this flash-of-lightning moment is reserved for the Valkyrie, the true heroine of the opera, highlights Zambello's concept: nothing much distracts from the focus on the Valkyrie's central role. Wagner's intentions are perfectly served by underlining her disobedient (and thus revolutionary) love as the central counter-force against the ultimately impotent love and doomed power of the Gods. The long scenes of father-daughter intimacy and quarrel carry an intensity and suspense that equals Chéreau's because of the way Brünnhilde reacts to Wotan: Nina Stemme brings an emotional intelligence and subtle body language to these scenes that makes them fascinating to watch and listen to, moment by moment.

|

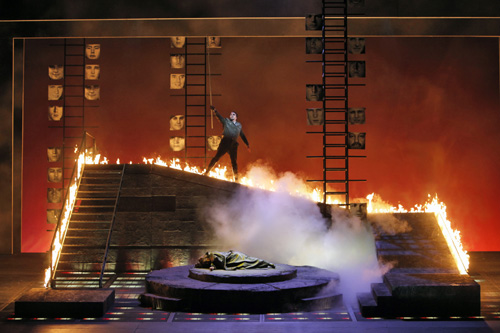

In Act III, on the Valkyrie rock, Brünnhilde is of course surrounded by her eight Valkyrie sisters (sired by Wotan with Erda, the embodied Earth) – all in the aviator garb of pioneers, eight buoyant would-be Amelia Earharts, sporting long aviator scarves and binos on their necks. They hang-glide onto the stage as if coming down with parachutes, bringing the house down. To the stirring, full-orchestra blow-out of their gallop, the sexy-androgynous troop merrily climbs all over the rock in pants that stretch across some hefty backsides. The brief moment of comic relief quickly turns serious, however, when a procession of soldiers from different American wars silently, like in a ghostly vision, moves across the stage –the dead heros the Gods collect for their own futile protection from evil. Instead of the usual dragging around dead warriors, the Valkyries here gather and carry LP-size disks with the slate-colored faces of fallen soldiers from Irak and Afghanistan – the same faces we have been watching nightly, in silence, on the News Hour. They attach the portraits to totem-like metal scaffolding, building a strangely compelling memorial to the victims of God and men's "holy wars." With these images, Zambello goes daringly close to an edge of over-stretching the contemporary relevance, even close to "war kitsch," but the risk pays off. Usually the Valkyries -- Wagner's hefty Germanic "amazons" with breast-plates and horned helmets-- are something of a laughing stock; in spite of their rousing, fantastical music they make one smile about their mildly absurd anachronism. Zambello turns the sisters into a serious paratrooper formation under Wotan's command, and their horror and lament over Brünnhilde's degradation is played out as a ferocious battle between military, male-type control and unleashed female emotion. For once, the Valkyries are a superbly acted, intense part of the drama between father and daughter, obedience and rebellion, power and love. (The excellent choreography is by Lawrence Pech.)

|

When Zambello's Brünnhilde faces the raging God alone to receive her punishment for her betrayal (she will be cast out, stripped of her divinity and fall under the spell of sleep, awaiting a humiliating human destiny), she doesn't beg or plead like a vulnerable female. She argues. She still assumes she is an equal in spirit, and most of the time Zambello places her above Wotan on the fatal rock. The father God holds the power but she holds the morally higher position, which Wotan can't resist recognizing.

American baritone Mark Delavan (who came up through the Merola Opera Program and was an Adler Fellow) has made a huge leap in his portrayal of Wotan. With vocal heft and ferocious authority, his acting now makes him a believably thoughtful, deep-feeling power broker who is caught in his own snares by the bad contracts he made (both the historical and contemporary echos of economic follies are palpable) and by his wily wife Fricka who reads him like a book.

|

The triumph of Brünnhilde as the central, modern heroine has a cost, however. The usual romantic highlight of the opera, the incestuous love of the twins Siegmund and Sieglinde, lacks luster by comparison. I wish Zambello had seen Debra Granik's new film Winter's Bone before designing her Act I in a simple clapboard house in the forest, complete with screen door, dear heads on the walls and cheap tchotchkes on the shelves. The hillbilly women in Granik's film could have given her some clues on how to take her Sieglinde (Dutch diva Eva-Maria Westbroek) far beyond the creepy, co-dependant cowering she shows toward her white trash, vigilante husband Hunding. Everything here is overacted and overly obvious: American bass Raymond Aceto's Hunding shows every moment that Sieglinde (in an apron-like house dress, with bruised arms) is his hostage and his prize possession; he doesn't let her out of his slimy grip. Her abject, fussy obedience, rushing to fetch one beer after another to placate him, is so embarrassing to watch that one hardly pays any attention to Siegmund (British tenor Christopher Ventris) whose tales of woe, in a more coherent version of Act I, would take center stage. Part of the problem is that neither man has real power; Aceto's Hunding lacks vocal menace; he is a loser from the get-go; Ventris's Siegmund has a beautiful voice but his lumbering, hunched physicality makes him unconvincing as a hero rebel and half-God. Westerbroek as Sieglinde has a compelling, burnished voice that later, in her despair, attains dramatic conviction, but her broken, inexistent spirit literally drowns her in dish water. The weak chemistry between the twins lacks the even more crucial elements of a larger-than-life passion that transcends human lore and divides the Gods. Forget the Gods, Zambello here makes the same miscalculation she made in Rheingold: you banalize the mythical story of the Ring at your own risk and peril.

|

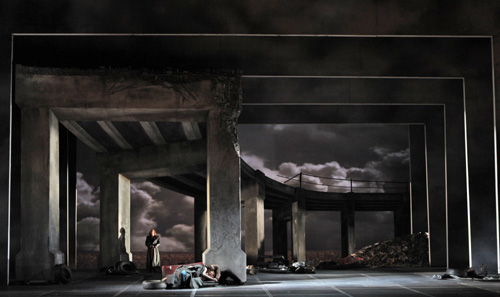

Fortunately she almost instantly recovers her wits and turns her vigilante idea into a modern nightmare in the next scene (Act II) when Siegmund and Sieglinde flee from Hunding and end up in the desolate junk of a broken off freeway overpass. A rotten sofa holds the fainting Sieglinde. The approach of Hunding's men comes like a Twilight invasion of the undead: two big dogs suddenly cross the stage, followed, as in a very bad dream, by a nimble, shadowy group of gang-members in woollen caps. It seems the inevitable continuation of the frozen spell when first Siegmund, then Hunding falls without any direct interference by the gods who are all gathered around in that spookish dawn.

Chéreau ended the scene with Wotan's wrath, his furious pursuit of Brünnhilde. Zambello gives Brünnhilde the final scene. She hurries back with Sieglinde to gather up the pieces of Siegmund's sword while Wotan avoids looking. The Valkyrie again is shown as the crucial agent, the culminating force of the drama. So perhaps the first prize in the costume contest was deserved, after all: one spectator had recognized and named the feminist bend of this production correctly.

Photos - Cory Weaver

(except as otherwise noted)

|

|